Dulwich, London

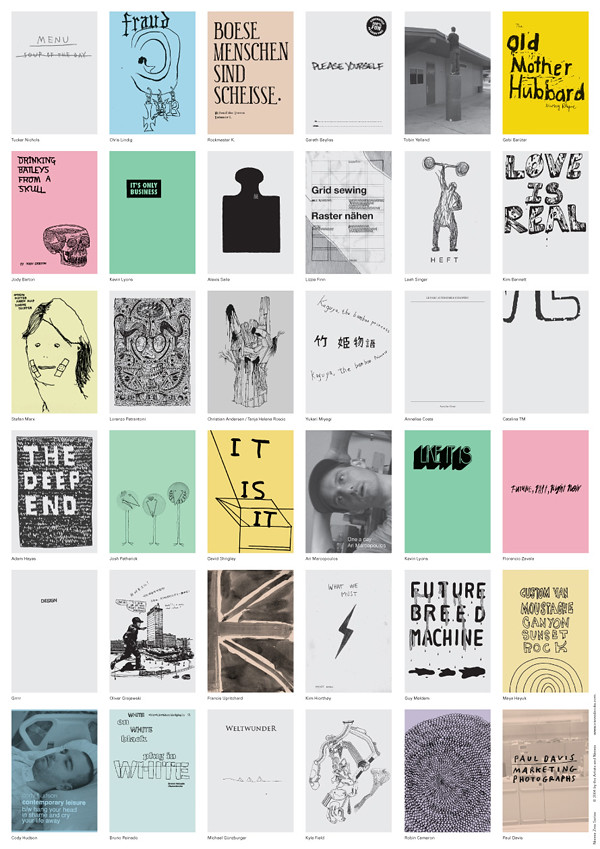

PORTRAITS OF SELECTED FACADES

Bill*, originally from Yorkshire, lives on ____ Street, in a small Victorian bay-fronted terrace. Perched on the bay window’s roof is a large illuminated Father Christmas in a sleigh, still greeting passers-by in mid-January. The windows themselves have been replaced with UPVC casements, the bedroom ones framing a pair of satellite dishes. Bill’s e-mailed reply to my letter stipulated that his Portuguese partner, the housekeeper, had requested that I did not visit; the uninvited step into the hall. He is a former mechanic and, as such, is the only person I communicated with in Camberwell and Peckham who could claim to be ‘working class’. He is modest about the scale of his home improvements; when asked what he has changed about his exterior he cites ‘just windows, walls, and tiling’ (Bill to Stewart, 2010), but I suspect he may have been responsible for the front door with its wrought iron ‘Olde English‘ decorative hinges. The ‘front garden’ - a strip of about 1.5 metres between the facade and the pavement - has been fully tiled in pale ceramic, of the kind more usually found in kitchens and conservatories, and the boundary wall is of cerise roughcast, topped with concrete, acorn-shaped finials. It is tempting to link these decorative quirks to his wife’s roots in more clement Portugal, but Bill does not think his house reflects them as people in any way, although he does say that ‘If it looks clean outside then 9/10 [houses] are clean inside.’

The ______ Estate is further in the direction of suburbia ‘proper’. Its prefabricated bungalows were intended as temporary ‘Homes for Heroes’ after the Second World War. Twenty nine are now owner-occupied. Their exteriors have been subject to a wide variety of treatments, from those where the strapping joining the prefabricated panels has been highlighted in black to give the effect of half-timbering to one with a skin of yellow facing brick, passing itself off as a conventional bungalow. Many of the houses display St George’s flags, or plaques with sentiments ranging from ‘Home Sweet Home’ to ‘BEWARE OF THE DOG’.

Barbara, a local, was lucky to acquire hers after her builder husband’s aunt passed away. They and their two children had been renting a flat nearby but when the opportunity for some ‘peace and quiet’ (Barbara to Stewart, 2010) and their own piece of garden arose they jumped at it. Their house is painted in a soft pink and the front door incorporates a mock Georgian fanlight and shiny gold-coloured doorknocker. Barbara tells me they would probably replace the windows if it weren’t for the lingering threat of demolition. Another resident, catching me taking photographs and keen to talk about the community’s plight, informs me that owners have been offered £30,000 each for their homes, a figure which in London property terms means the houses are virtually worthless. Ironically, it is only six unloved-looking and therefore untouched prefabs on the estate which have been given a grade II listing and might therefore escape the fate of the others. (Blackender, 2009)

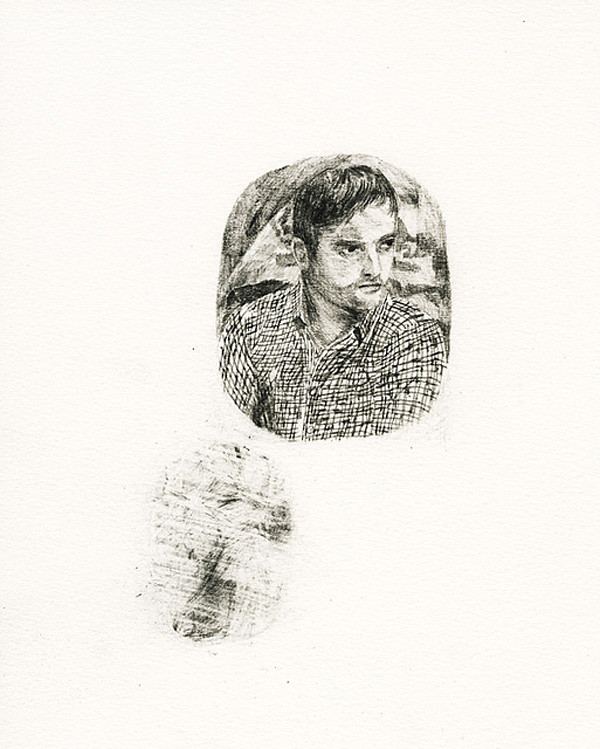

Christmas is a presence at Claire’s on Camberwell’s _____ Street too, in the form of paper snowflakes in the sash windows - recently installed double glazed timber replicas, she informs me, to replace ‘horrible plastic things’ (Claire to Stewart, 2010) put in by the previous owners. The decision, I’m told, was ‘purely aesthetic.’ Their surrounds (Claire thinks they might be real stone) have been partially stripped of paint and the front garden features globe artichokes grown in a collection of requisitioned containers and a rough wooden signpost reading ‘CHATEAU PARADISO’.

Claire invites me into her kitchen (unfitted, distressed paintwork and children’s drawings everywhere) where she tells me that the exterior of her house does reflect herself in that she likes everything to be homemade; she is not interested in ‘the latest kitchen or things from catalogues.’ Claire is a wigmaker who graduated in Fine Art from Camberwell College twenty years ago, and her husband is an artist. She likes the range of exterior treatments in her street - ‘difference is marvellous, key’ - and suggests that this is an urban virtue, distinguishing the area from ‘the suburbs’, where ‘people morph into the same thing over and over again.’

By the time I receive contact from Brett (artist, designer and author) two streets away it’s clear that around here it is going to be challenging to solicit feedback from people whose occupations aren’t connected with aesthetics. This ought to be less of a surprise than it is; after all, I did not select houses entirely at random. Perhaps I have chosen an area with too high ‘a minority of freaks and intellectuals.’ (Richards, 1973 p.15)

Brett’s house has a pea green front door whose fanlight displays a carefully proportioned typographic house number designed by Brett himself. Eclectic objects are arranged around the door: animal skulls, rusty pieces of metal and dried seedheads. Brett is succinct about the function of this: ‘For someone visiting your house for the first time it's (sic) appearance is like a visual handshake.’ (Brett to Stewart, 2010) He thinks his house reflects him ‘somewhat - although being a private home it's not a public statement.’

There is a property is on a section of Ferndene Road, Denmark Hill lined with Edwardian and 1920s semi-detached villas, displaying Arts and Crafts detailing. This house has been subject to a radical makeover; above the minimal front door is a plate glass floor to ceiling window in place of the original cosy casement and the garden’s boundary is no longer defined by basketweave brickwork but by Brutalist concrete. I receive no response but when posting my letter I catch a glimpse of open plan white space within.

Julia’s house on ______ Street or ‘South London’s finest Georgian street’ (Wooster Stock, 2009) in estate agents’ terms, employs the classic Georgian device of variation in window sizes to denote the hierarchy of the storeys, from the piano nobile on the first floor to the mansard dormers. The grey paint on the lintels is flaking, in contrast to the black (previously red – the change was thought ‘more in keeping’) front door with its highly polished brass lion doorknocker. Julia is yet another ‘creative’ - an interior designer - and her husband ‘works in the City’ (Julia to Stewart, 2010). Julia says the appearance of her house is important to her ‘especially in a street like this’, and ‘it’s a bit of a cliché but I do think the garden is another room. I like it to reflect the interior’; she ‘loves the formality of the box hedging and bay trees’.

(*I've changed names, removed street names and some other details)